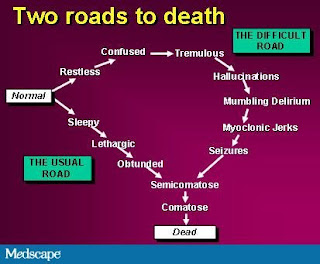

Two Roads to Death: The Usual Trajectory

Decreasing Level of Consciousness

Most patients traverse the "usual road to death." They experience increasing drowsiness, sleep most if not all of the time, and eventually become unarousable. Absence of eyelash reflexes on physical examination indicates a profound level of coma equivalent to full anesthesia.Communication with the unconscious patient. Families will frequently find the inability to communicate with their loved one distressing. The last hours of life are the time when they most want to communicate with their loved one. As many clinicians have observed, the degree of family distress seems to be inversely related to the extent to which advance planning and preparation occurred. The time spent preparing families is likely to be very worthwhile.

Although we do not know what unconscious patients can actually hear, extrapolation from data from the operating room and "near death" experiences suggests that at times their awareness may be greater than their ability to respond. Given our inability to assess a dying patient's comprehension and the distress that talking "over" the patient may cause, it is prudent to assume that the unconscious patient hears everything. Advise families and professional caregivers to talk to the patient as if he or she were conscious.

|

| Credit: Medscape Internal Medicine |

- "I know that you are dying; please do so when you are ready."

- "I love you. I will miss you. I will never forget you. Please do what you need to do when you are ready."

- "Mommy and Daddy love you. We will miss you, but we will be okay."

The More Difficult Road to Death: Terminal Delirium

Terminal delirium. An agitated delirium may be the first sign to herald the "difficult road to death." It frequently presents as confusion, restlessness, and/or agitation, with or without day-night reversal. To the family and professional caregivers who do not understand it, agitated terminal delirium can be very distressing. Although previous care may have been excellent, if the delirium goes misdiagnosed or unmanaged, family members will likely remember a horrible death, "in terrible pain," and cognitively impaired "because of the drugs," and they may worry that their own death will be the same. Bruera and associates have documented the distressing impact of delirium on patients and families.In anticipation of the possibility of terminal delirium, educate and support family and professional caregivers to understand its causes, the finality and irreversibility of the situation, and approaches to its management. It is particularly important that all onlookers understand that what the patient experiences may be very different from what they see.

If the patient is not assessed to be imminently dying, it may be appropriate to evaluate and try to reverse treatable contributing factors such as pain, urinary retention, or severe constipation/impaction. The treatment of reversible delirium is to find and correct reversible causes. The drug class of first choice for symptomatic management of reversible delirium is the neuroleptics. On the other hand, irreversible delirium can also affect patients in the final hours of living. In this setting, it is referred to as irreversible terminal delirium. Irreversible delirium does not respond to conventional treatment for reversible delirium. Focus on the management of the symptoms associated with terminal delirium in order to settle the patient and the family.

When moaning, groaning, and grimacing accompany the agitation and restlessness, these symptoms are frequently misinterpreted as physical pain. However, it is a myth that uncontrollable pain suddenly develops during the last hours of life when it has not previously been a problem. Although a trial of opioids may be beneficial in the unconscious patient who is difficult to assess, clinicians must remember that opioids may accumulate and add to delirium when renal clearance is poor. If the trial of opioids does not relieve the agitation or makes the delirium worse by increasing agitation or precipitating myoclonic jerks or seizures (rare), then pursue alternative therapies directed at suppressing the symptoms associated with delirium.

Currently, no studies specifically address the management of terminal delirium. Palliative experts base their treatment recommendations on the goals of treatment and the mechanisms of action of classes of medication. Benzodiazepines are generally not recommended for first-line management of delirium, especially if the delirium is thought to be reversible, because they can worsen delirium and cause paradoxic excitation. However, because they are anxiolytics, amnestics, skeletal muscle relaxants, and antiepileptics, benzodiazepines are recommended by palliative care experts for the management of irreversible terminal delirium, where the goal of therapy is sedation. Benzodiazepines are also the drug class of first choice for management of delirium complicated by seizures or caused by alcohol or sedative withdrawal. Common starting doses are:

- Lorazepam, 1-2 mg as an elixir, or a tablet predissolved in 0.5-1.0 mL of water and administered against the buccal mucosa every hour as needed until agitation subsides. Most patients will be controlled with 2-10 mg per 24 hour period. It can then be given in divided doses, every 3-4 hours, to keep the patient calm. For a few extremely agitated patients, high doses of lorazepam, 20-50+ mg/24 hours, may be required.

- Midazolam 1-5 mg/hour subcutaneously or intravenously by continuous infusion, preceded by repeated loading boluses of 0.5 mg every 15 minutes to effect, may be a rapidly effective alternative.

If benzodiazepines cause paradoxical excitation, the patient may require neuroleptic medications to control delirium. Haloperidol has fewer sedating and hypotensive effects, but in bedbound patients in whom sedation is desirable, chlorpromazine is a better choice:

- Chlorpromazine 10-25 mg orally or rectally every 60 minutes, or subcutaneously/intravenously every 30 minutes until agitation is controlled. Titrate to effect, then give the summed dose nightly to every 6 hours to maintain control.

- Haloperidol 0.5-2.0 mg intravenously every 10 minutes, subcutaneously every 30 minutes, or rectally every hour until agitation is controlled (titrate to effect, then give the summed dose nightly to every 6 hours to maintain control).

Source:

The above article is reproduced from material entitled 'The Last Hours of Living: Practical Advice for Clinicians' by Medscape Internal Medicine. Retrieved 22.02.2011 from here and here. Note: Materials may be edited for content and length.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Got something to say? We appreciate your comments: